|

How entertaining? ★★☆☆☆

Thought provoking? ★★☆☆☆ 2 January 2008

This a movie review of TOKYO. |

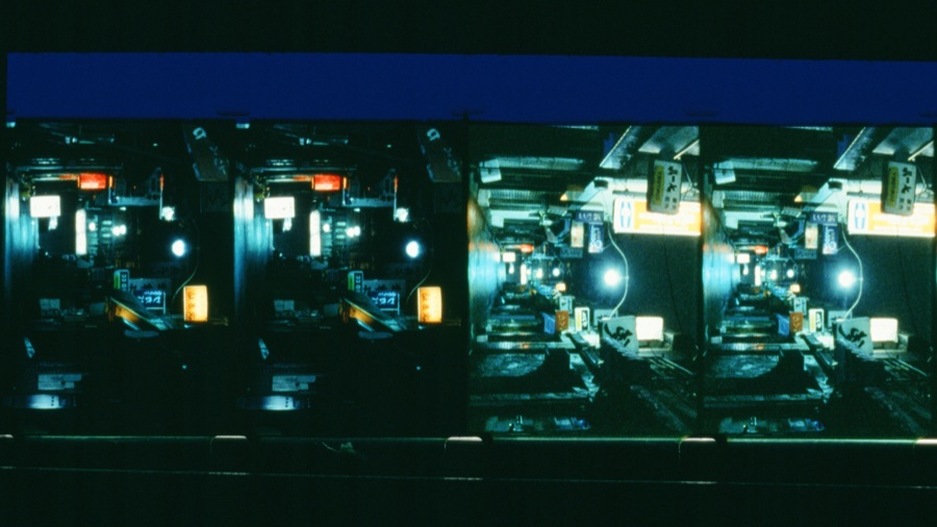

“This game induces a kind of hypnosis. Winning is hardly important. But, time passes, you lose touch with yourself for a while, you merge with the machine, and perhaps, you forget, what you always wanted to forget,” Wim Wenders

Released in 1985, acclaimed director Wim Wenders (PARIS, TEXAS; WINGS OF DESIRE; and BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB) made this documentary as a personal journey to Tokyo searching for the city depicted in the films of one of Wenders’ favourite filmmakers, Yasujiro Ozu – director of TOKYO STORY, among others, a film regarded by many as a masterpiece. Scenes from this film open and close TOKYO-GA, framing the documentary symmetrically.

Wenders narrates his own film, commencing with an ode to Ozu about how he depicted Tokyo and its people over 40 years; how Ozu showed the slow deterioration of the Japanese family and thereby the deterioration of the Japanese identity – though Ozu’s films are universal, cinema in its purest form states the narrator. TOKYO-GA is a filmed diary (starting in spring 1983) to see since Ozu’s death twenty years earlier what remains of Ozu’s portraits of Tokyo.

Wenders wonders whether he would have better remembered his time in Tokyo without the camera. The director ponders if it is possible to film like when you just open your eyes: to look without wanting to prove anything. He says Tokyo is like a dream, and the footage barely equates with his memories. It is perhaps interesting that in David Lynch’s 1997 film LOST HIGHWAY, Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) states he does not like camcorders because they do not concur with his memories.

Released in 1985, acclaimed director Wim Wenders (PARIS, TEXAS; WINGS OF DESIRE; and BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB) made this documentary as a personal journey to Tokyo searching for the city depicted in the films of one of Wenders’ favourite filmmakers, Yasujiro Ozu – director of TOKYO STORY, among others, a film regarded by many as a masterpiece. Scenes from this film open and close TOKYO-GA, framing the documentary symmetrically.

Wenders narrates his own film, commencing with an ode to Ozu about how he depicted Tokyo and its people over 40 years; how Ozu showed the slow deterioration of the Japanese family and thereby the deterioration of the Japanese identity – though Ozu’s films are universal, cinema in its purest form states the narrator. TOKYO-GA is a filmed diary (starting in spring 1983) to see since Ozu’s death twenty years earlier what remains of Ozu’s portraits of Tokyo.

Wenders wonders whether he would have better remembered his time in Tokyo without the camera. The director ponders if it is possible to film like when you just open your eyes: to look without wanting to prove anything. He says Tokyo is like a dream, and the footage barely equates with his memories. It is perhaps interesting that in David Lynch’s 1997 film LOST HIGHWAY, Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) states he does not like camcorders because they do not concur with his memories.

|

|

|

1980s Tokyo is illustrated with images of the cityscape, businessmen eating a picnic in a cemetery with cherry blossoms, a person reading manga, and the underground train system with high-tec tube maps. Wenders says that Ozu’s films made Tokyo seem intimate and familiar, and he wants to rediscover this familiarity. The director’s camera is trying to find this intimacy; illustrated by capturing a rebellious little boy who does not want to take another step like the rebellious children of Ozu’s work – or maybe Wenders admits he wants to recognise, but actually what he is searching for no longer exists.

There is a recurring image of the pinball-style arcade parlours that had become popular since the Second World War. Rows of players sit next to each other, but the director surmises that this heightens the isolation of the solo game. Wenders hypothesises the hypnotic effect of the game numbs the pain of the Second World War. All generations play at the parlours and perhaps the statement is too sweeping an analysis?

Wenders is critical of current Tokyo, with television to blame – the wealth of images being destructive; though he admits that Ozu’s films are works of fiction, made in a different time, and perhaps metaphorical.

The director interviews one of Ozu’s actors, Chishu Ryu, who usually plays the father. Ryu says the main thing about acting in the director’s films was to carry out precisely his instructions. Even though they were only a year apart, Ryu admits Ozu had a superior intellect, he was the master and Ryu was the pupil. Ryu says the filmmaker was a perfectionist.

Wenders visits the cemetery where Ozu is buried, but the grave is unmarked bar a Chinese character which means “emptiness” or “nothingness”. And as a result the director meditates on the relationship between cinema and reality. People are so accustomed to seeing a clear delineation between cinema and reality that they gasp when they see a portrayal of truth, even if it is just a small gesture. People’s personal reality as they see reality is rarely shown. Wenders claims that Ozu’s films were truthful in the depiction of reality, no longer is anyone depicting this.

TOKYO-GA is an unusual lesson for all cineastes. It is a dissection of cinema and its impact, and an original look at an acclaimed filmmaker looking at an acclaimed filmmaker.