|

★★★★☆

14 June 2007

This article is a review of BLACK RAIN. |

Osaka, Japan.

A cop on the edge.

A conspiracy on the rise.

A killer on the loose.

The poster’s tag-line is a succinct intro to this super-stylish 1989 thriller from the magnificent Ridley Scott (ALIEN, GLADIATOR, BLADE RUNNER). However, there is more going on than just an apparently conventional cop movie. Star Michael Douglas and director Scott are anything but conventional. Douglas has the flawed American male sown up: WALL STREET, FATAL ATTRACTION, WONDER BOYS, THE GAME, TRAFFIC, to name a few; and Scott is a visual master.

BLACK RAIN is one way how late 80s America viewed Japan, both positively and negatively and with arguable sweeping judgements, through the prism of a cop thriller. The Paramount studio logo in the intro fades to a red disc that in turn fades to a large statue of a globe where America is the country on view. This symbolism of the Japanese flag over the United States sets the tone for the culture clash that is about to ensue.

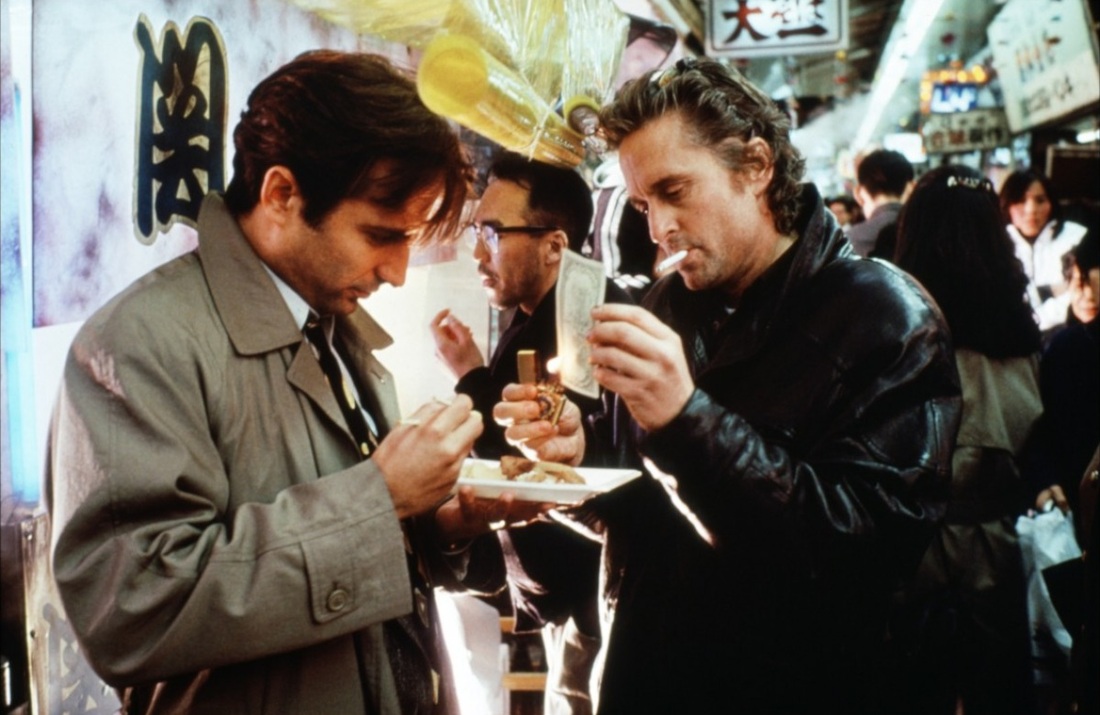

“I don’t like the heroes Conklin they think the rules don’t apply”, Internal Affairs. Nick Conklin (Douglas) is called a hero on more than occasion in BLACK RAIN; a decorated officer as well as a maverick (aren’t all movie cops?), but allegations of corruption hang over him, and when he ends up in Japan a racist streak comes through. He is perhaps a cipher for what is good and bad about Americans in the eyes of the Japanese. His friend, and fellow police officer, Charlie Vincent (Andy Garcia) represents the new America, “Ladies of the Eighties are going for shoes...They say it’s the second place they look.” He is well-dressed, curious, interested, superficial, naive and a diplomat. These two are America’s ambassadors in Japan.

A cop on the edge.

A conspiracy on the rise.

A killer on the loose.

The poster’s tag-line is a succinct intro to this super-stylish 1989 thriller from the magnificent Ridley Scott (ALIEN, GLADIATOR, BLADE RUNNER). However, there is more going on than just an apparently conventional cop movie. Star Michael Douglas and director Scott are anything but conventional. Douglas has the flawed American male sown up: WALL STREET, FATAL ATTRACTION, WONDER BOYS, THE GAME, TRAFFIC, to name a few; and Scott is a visual master.

BLACK RAIN is one way how late 80s America viewed Japan, both positively and negatively and with arguable sweeping judgements, through the prism of a cop thriller. The Paramount studio logo in the intro fades to a red disc that in turn fades to a large statue of a globe where America is the country on view. This symbolism of the Japanese flag over the United States sets the tone for the culture clash that is about to ensue.

“I don’t like the heroes Conklin they think the rules don’t apply”, Internal Affairs. Nick Conklin (Douglas) is called a hero on more than occasion in BLACK RAIN; a decorated officer as well as a maverick (aren’t all movie cops?), but allegations of corruption hang over him, and when he ends up in Japan a racist streak comes through. He is perhaps a cipher for what is good and bad about Americans in the eyes of the Japanese. His friend, and fellow police officer, Charlie Vincent (Andy Garcia) represents the new America, “Ladies of the Eighties are going for shoes...They say it’s the second place they look.” He is well-dressed, curious, interested, superficial, naive and a diplomat. These two are America’s ambassadors in Japan.

While having lunch in New York they witness a brutal yakuza double homicide in a restaurant (where an unidentified box is stolen) and detain the perpetrator, Sato (Yasuka Matsuda), only to have the Japanese US Embassy require Sato’s extradition to Osaka to face trial there. Conklin and Vincent babysit the ruthless killer back to Japan. (Conklin likes to smoke and is happy to light up in the plane – shows how things have changed in the last 18 years). The flight into Osaka reveals a stunning dawn vista with industrialisation and cityscapes rarely looking as beautiful. We have entered industrialised Japan with high plumes of smoke from factories and buildings as far as the eye can see. Music containing Japanese drums and strings signal a significant shift in what is about to face these two.

Once on Japanese soil, and not even off the plane, gangsters posing as police showing documentation in Japanese (and unreadable to the Americans) rescue Sato from custody. As Sato leaves the plane a rivalry that began in New York is cemented as his hands form a prayer and then fold into a gun shape – a threatening religious tinge whatever your beliefs – Buddhist or Christian or whichever your faith.

A fish-out-of-water scenario presents itself. Shown mug-shots of criminals Conklin cannot identify anyone, implying that he feels all the local suspects look alike, and that racism is made explicit when he utters a slur concerning nobody speaking English. The prolonged negotiations, with the Osaka Superintendent, to be allowed onto the case hints at the film’s feeling that the authorities in general, and the nation as a whole, are methodical contemplators, slow, formal, diligent, minimal risk-takers, secretive, proud, patient, polite and thorough, to the point of excruciating frustration to the hot-headed Americans. This scene with the two police forces is a very clever reveal to what the film is also about - the culture-clash of misunderstanding, rivalry, good intentions and animosity. The United States and Japan have a complicated and emotional relationship, and these themes are hung on the bones of an action-thriller.

Hailed as incompetent by the Osaka police and press, and Conklin suspected of being bought off by Sato by the New York authorities back at home, mean they force themselves on to the Osaka investigation but only as observers. They begin to play the subtle game, they dangle losing face and scandal to barter their way on to the chase for Sato. Thus the poster tag-line comes to fruition: Conklin is on the edge with his career in the balance, Sato is the killer on the loose, and the conspiracy...

Joyce (Kate Capshaw), “You could get me killed detective. You see there’s a war going on here and they don’t take prisoners.”

Conklin, “What are you talking about?”

Joyce, “Between Sato and an old-time boss, a guy named Sugai.”

Conklin, “Who else knows about this?”

Joyce, “Counting you and me?”

Conklin, Yeah.”

Joyce, “Eleven million.”

Steven Spielberg’s wife Capshaw plays a blonde hostess from Chicago (resident in Japan for seven years) in one of Osaka’s trendy bars, and plays a sort of reluctant guide to Conklin. “No one is going to help a gaijin – a stranger, a barbarian, a foreigner. Me and you,” Joyce. The film portrays Conklin and Vincent all alone, where the customs are alien and no-one will help. But over time comes a mutual respect and friendship with those around them, in particular a Japanese cop assigned to them, Masahiro (Ken Takakura). The three officers represent the love-hate relationship between the countries, with the men as a symbol for the strengths, flaws and contradictions of their homelands.

Osaka is shown to be a beautiful yet daunting place. Neon corporatism is in full splendour - “Kenwood”, “Asahi” or “Nikon” signs attached to buildings hark back to Scott’s earlier film, BLADE RUNNER, a sci-fi rendition of Los Angeles which in the future has been massively influenced by Japan. BLACK RAIN also has real attention to detail: the atmospheric phosphorescence of the lighting, the steam billowing around pedestrians, smoke plumes and striking production design. There is very little sign of old Japan, until the climax in the countryside. We also see a night scene of the impressive city golf-range, the bustle of Osaka market, the immensity of the steel works, the contrast of high-rise and mansion living, and the studiousness of a police HQ.

Black Rain is a sumptuous thriller. If only more of the mainstream had its panache.